By Nik Money

•

August 9, 2025

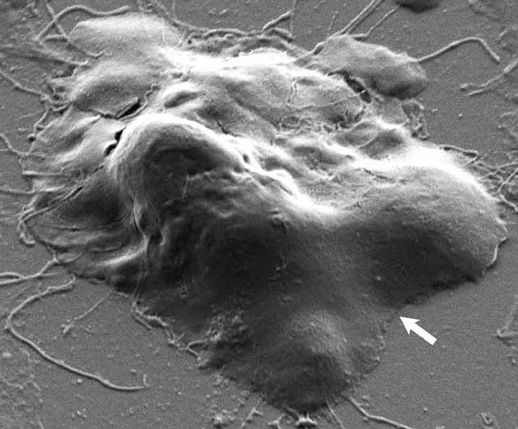

[Image of amoeba adapted from A. Cassiopeia Russell, et al., Frontiers in Microbiology 14 (2023):1264348.] A brain-eating amoeba called Naegleria has received a lot of recent media coverage, including the tragic deaths of a 12-year-old boy in South Carolina who swam in a local reservoir, and a 71-year-old Texas woman who had flushed her sinuses with a neti pot. Using anything other than sterilized water in a neti pot is a proven hazard, but should we be concerned about splashing around in lakes and rivers? This post describes the infection process, explains why cases of this terrible illness may be increasing, and considers the risks of summer recreational activities in our rivers. There have been fewer than 200 cases of this infection in America in the last 50 years and all of these deaths resulted from the nasal inhalation of warm water contaminated with the microbe. There are thousands of species of microbes that we call amoebas because they crawl in a similar fashion to the iconic “classroom” amoeba, Amoeba proteus , which is recognized from the simplest drawing of a wavy outline with a dot in the middle. Naegleria is as distantly related to Amoeba as a rhinoceros is to a rhododendron, but it moves in the same shape-shifting fashion. Unlike the schoolroom amoeba, however, Naegleria can also swim by sprouting a pair of flagella. At one time it was thought that the frisky swimming stage was the one that infected humans, but the crawling cells that gather at the surface of the water are actually more dangerous because they are positioned perfectly for snorting high into the nasal cavities of swimmers. The migration of the amoebas from the nose to the brain is circuitous because the head jelly is enclosed in the skull, wrapped in membranes called meninges, and protected by a formidable tissue layer called the blood-brain barrier that separates the bloodstream from the central nervous system. Trauma to the head that damages these shields can lead to infections, but even an uninjured nose is an anatomical liability for anyone who encounters a pathogenic amoeba. This does not mean that everyone who inhales water carrying the amoebas will become infected—far from it. Mucus that lines the nasal sinuses works as a sticky trap and antibodies bind to the amoebas interfering with their attempts to attach to the tissues underneath. The amoebas are also attacked by white blood cells called neutrophils as they try to get a good foothold on the sinus tissues. As the neutrophils close in, like bloodhounds set loose on fugitives, the amoebas reshape their membranes into suction cups and tear into the fleshy tissues of the sinuses to escape. The odds are stacked against the amoebas, but any that follow the nerves that snake through perforations in the bony roof of the nose have the chance of reaching the brain. The escapees leave the neutrophils howling in the sinuses and the prognosis for the swimmer is grim. Headaches, fever, neck stiffness, nausea, and vomiting occur within as little as a day after exposure, and the symptoms proceed to light sensitivity, seizures, hallucinations, coma, and death. Physicians call this brain infection primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM. Treatments are very limited. A drug called miltefosine that has been used to treat a tropical disease called leishmaniasis for more than 20 years is showing promise as a new medicine for PAM patients. This makes sense because the parasite that causes leishmaniasis belongs to the same supergroup of microorganisms as Naegleria . The importance of finding treatments for PAM is increasing with the concern expressed by epidemiologists that these infections are likely to become more common as the planet gets warmer and the geographical range of the microbe widens. Warming lakes and rivers will certainly advantage this amoeba, which is happiest in water with temperatures between 30 and 42 degrees Celsius, or 86 to 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Naegleria fatalities have already been reported in India, China, and Southeast Asia. Countries with cooler climates may not escape from this public health threat. Water used to cool nuclear and conventional power plants can support high levels of the amoeba, which represents a source of potential infections when the heated water is discharged into rivers and lakes. The Centers for Disease Control recommends holding your nose shut or using a nose clip if you jump or dive into a river. This provides little comfort. We know that the amoeba finds its way into the brain from the nasal passages, but the rarity of the infection suggests that there may be more to this than inhaling the microbe through the nostrils. Neti pot users increase the pressure within their nasal passages as they rinse and expel water, which may have the effect of forcing the microbe into these sensitive tissues. This leads me to wonder whether swimmers could be safer without nose clips, because closure of the nostrils prevents the reflexive expulsion of water pushed into the back of the throat. Knowledge of the amoeba leaves us with a feeling of unease. The development of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis after playing in a river or lake is less likely than drowning, but this fact is of little comfort to anyone who contracts the brain disease. So, what do we do? Shrug our shoulders, hope for the best, fear the worst, and jump from a rope swing into the river. After all, amoebas and other microbes are everywhere and will outlive us by an eternity.