PASTURES NEW

The evolutionary kinship of the fungi and animals is indicated by their combination into a single supergroup of organisms called the opisthokonts . This uninspiring term refers to the arrangement of shared cell structures called cilia. I suggest that we adopt a more evocative name: mycozoans .

[Image of amoeba adapted from A. Cassiopeia Russell, et al., Frontiers in Microbiology 14 (2023):1264348.] A brain-eating amoeba called Naegleria has received a lot of recent media coverage, including the tragic deaths of a 12-year-old boy in South Carolina who swam in a local reservoir, and a 71-year-old Texas woman who had flushed her sinuses with a neti pot. Using anything other than sterilized water in a neti pot is a proven hazard, but should we be concerned about splashing around in lakes and rivers? This post describes the infection process, explains why cases of this terrible illness may be increasing, and considers the risks of summer recreational activities in our rivers. There have been fewer than 200 cases of this infection in America in the last 50 years and all of these deaths resulted from the nasal inhalation of warm water contaminated with the microbe. There are thousands of species of microbes that we call amoebas because they crawl in a similar fashion to the iconic “classroom” amoeba, Amoeba proteus , which is recognized from the simplest drawing of a wavy outline with a dot in the middle. Naegleria is as distantly related to Amoeba as a rhinoceros is to a rhododendron, but it moves in the same shape-shifting fashion. Unlike the schoolroom amoeba, however, Naegleria can also swim by sprouting a pair of flagella. At one time it was thought that the frisky swimming stage was the one that infected humans, but the crawling cells that gather at the surface of the water are actually more dangerous because they are positioned perfectly for snorting high into the nasal cavities of swimmers. The migration of the amoebas from the nose to the brain is circuitous because the head jelly is enclosed in the skull, wrapped in membranes called meninges, and protected by a formidable tissue layer called the blood-brain barrier that separates the bloodstream from the central nervous system. Trauma to the head that damages these shields can lead to infections, but even an uninjured nose is an anatomical liability for anyone who encounters a pathogenic amoeba. This does not mean that everyone who inhales water carrying the amoebas will become infected—far from it. Mucus that lines the nasal sinuses works as a sticky trap and antibodies bind to the amoebas interfering with their attempts to attach to the tissues underneath. The amoebas are also attacked by white blood cells called neutrophils as they try to get a good foothold on the sinus tissues. As the neutrophils close in, like bloodhounds set loose on fugitives, the amoebas reshape their membranes into suction cups and tear into the fleshy tissues of the sinuses to escape. The odds are stacked against the amoebas, but any that follow the nerves that snake through perforations in the bony roof of the nose have the chance of reaching the brain. The escapees leave the neutrophils howling in the sinuses and the prognosis for the swimmer is grim. Headaches, fever, neck stiffness, nausea, and vomiting occur within as little as a day after exposure, and the symptoms proceed to light sensitivity, seizures, hallucinations, coma, and death. Physicians call this brain infection primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM. Treatments are very limited. A drug called miltefosine that has been used to treat a tropical disease called leishmaniasis for more than 20 years is showing promise as a new medicine for PAM patients. This makes sense because the parasite that causes leishmaniasis belongs to the same supergroup of microorganisms as Naegleria . The importance of finding treatments for PAM is increasing with the concern expressed by epidemiologists that these infections are likely to become more common as the planet gets warmer and the geographical range of the microbe widens. Warming lakes and rivers will certainly advantage this amoeba, which is happiest in water with temperatures between 30 and 42 degrees Celsius, or 86 to 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Naegleria fatalities have already been reported in India, China, and Southeast Asia. Countries with cooler climates may not escape from this public health threat. Water used to cool nuclear and conventional power plants can support high levels of the amoeba, which represents a source of potential infections when the heated water is discharged into rivers and lakes. The Centers for Disease Control recommends holding your nose shut or using a nose clip if you jump or dive into a river. This provides little comfort. We know that the amoeba finds its way into the brain from the nasal passages, but the rarity of the infection suggests that there may be more to this than inhaling the microbe through the nostrils. Neti pot users increase the pressure within their nasal passages as they rinse and expel water, which may have the effect of forcing the microbe into these sensitive tissues. This leads me to wonder whether swimmers could be safer without nose clips, because closure of the nostrils prevents the reflexive expulsion of water pushed into the back of the throat. Knowledge of the amoeba leaves us with a feeling of unease. The development of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis after playing in a river or lake is less likely than drowning, but this fact is of little comfort to anyone who contracts the brain disease. So, what do we do? Shrug our shoulders, hope for the best, fear the worst, and jump from a rope swing into the river. After all, amoebas and other microbes are everywhere and will outlive us by an eternity.

A screenplay by Matthew R. Riffle and Zackary D. Hill based on my 2017 novel, The Mycologist: The Diary of Bartholomew Leach, Professor of Natural History , is an official selection at the 2025 Cindependent Film Festival: https://www.cindependentfilmfest.org/ Wanda Sykes must be cast to play Phoebe Smith, Queen of Claysburgh. Excerpt: When Cates and I rode across the field, Phoebe Smith knocked out her pipe to prepare for battle: "Dare you is you damned whale; Cates haul you in again from offshore? You bin lying there sunnin your fat belly in Christ’s Sun I spose, hopin for a reeel high tide to pull you back to your damned porpuss-whore of a mother." I looked at Cates in utter amazement. He shrugged his shoulders and dismounted.

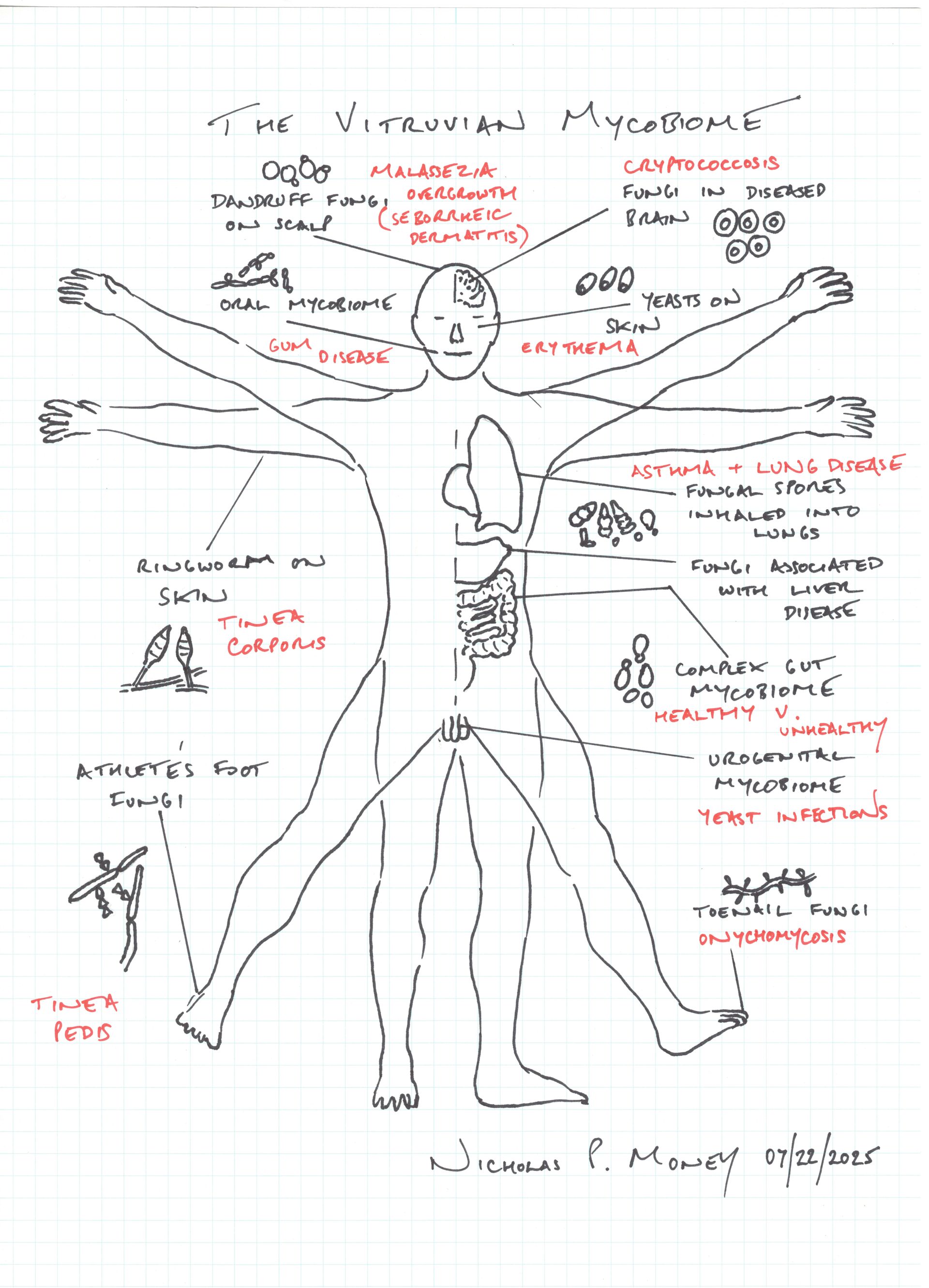

Dr. Gemma Anderson-Tempini is an artist working on a project about the mycobiome for a museum commission in Exeter in England. She asked several mycologists to “draw the mycobiome,” to help stimulate her thinking. This is my first draft in which I concentrated on the problems caused by fungi that live on the body. I could draw an alternative view to show that many of the same fungi are also part of the healthy microbiome. Interactions between fungi and bacteria is part of this story. Another approach would be to draw a mother nursing a baby and highlight the fungi in breast milk and the developing mycobiome of the infant.

With head-scratching among consumers about the sources of medicinal mushroom products, a reliable definition of a mushroom seems useful. Clarity is important because many of these “medicinals” come from mycelia instead of mushrooms and their chemical composition can be quite different. Here is my two-part definition. Mushrooms are the fungal equivalent of the fruits produced by plants. They release microscopic spores rather than seeds. We often refer to mushrooms as fruit bodies. Mushrooms are the reproductive organs of fungi. Their spores germinate to form feeding colonies called mycelia that grow as networks of branching filaments called hyphae. Mushrooms develop from mature mycelia to complete the fungal life cycle.

“What I have done . . . is to make a constructive contribution to the global conversation of science and to gain some measure of insight into that great mystery, the origin of life . . . The way of science is for the best of our achievements to endure in substance but lose their individuality, like raindrops falling into a pond. So let it be.” Frank Harold (2016) Click here for the tribute in full

A screenplay by Matthew R. Riffle and Zackary D. Hill based on my 2017 novel, The Mycologist: The Diary of Bartholomew Leach, Professor of Natural History , was an official selection at the 2024 Ink & Cinema Adapted Story Showcase. Click here for brief excerpt from the novel

With news of R.F.K. Junior’s encounter with a parasitic worm, I invite you to sing along with me to the tune of “My Favorite Things”: Roundworms in most guts and hookworms in plenty Segmented tapeworms that make you feel empty Many amoebas and pinworms like strings These were a few of our nightmarish things. (From “Molds, Mushrooms, and Medicines,” page 111)